Lithopedion – Mystery of the Stone Baby

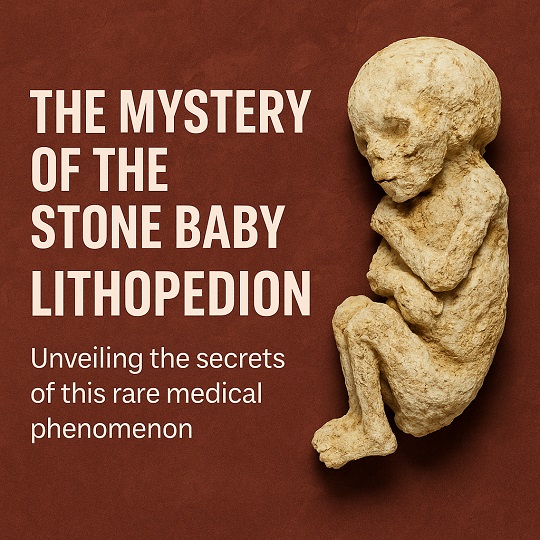

Lithopedion – Mystery of the Stone Baby. In the vast world of medical mysteries, few are as bizarre, haunting, and awe-inspiring as the phenomenon of lithopedion — also known as the “stone baby.” A condition so rare that only about 300 cases have ever been documented in medical history, lithopedion sits at the strange crossroads of obstetrics, pathology, and human resilience. It’s the kind of story that sounds like folklore — until you realize it’s real.

What Is Lithopedion?

The word lithopedion comes from Greek roots: “lithos” meaning stone and “paidion” meaning child. It refers to a rare condition in which a fetus dies during an ectopic pregnancy — typically in the abdominal cavity — and becomes calcified instead of being absorbed by the mother’s body. In simpler terms, the body turns the lost fetus into stone as a protective mechanism.

It’s a silent guardian of life that the body wasn’t ready to let go of, nor fully digest. The result: a fetal skeleton encased in calcium, lying dormant for years, sometimes decades, inside the mother’s body — often unnoticed.

How Does It Happen?

Lithopedion occurs in cases where the fetus dies during a non-viable ectopic pregnancy, usually after three months of gestation. Since the fetus is too large to be reabsorbed and is located outside the uterus — often in the peritoneal cavity — the mother’s immune system is faced with a dilemma. Instead of risking infection or inflammation by letting the fetus decay, the body coats it in calcium salts, essentially mummifying it into a sterile, stone-like mass.

This natural calcification prevents infection and allows the mother to continue life normally — often unaware of the silent presence inside her.

Who Does It Affect?

Lithopedion typically affects women in regions or eras where access to regular prenatal care or surgical intervention is limited. Many cases have been reported from rural or underserved areas. In some instances, women may not even realize they were pregnant or may have assumed a miscarriage occurred.

One of the oldest documented cases was found in a 68-year-old French woman who had unknowingly carried a lithopedion for 55 years. Her case shocked the medical community when discovered during an abdominal scan for unrelated issues.

A Glimpse into the Past: Historical Cases

One of the most well-known early cases was reported in 1582, when a 68-year-old woman in France complained of abdominal pain. Upon examination after her death, physicians discovered a calcified fetus that had been inside her for over 28 years. The case was documented by French surgeon Ambroise Paré and remains one of the earliest known medical accounts.

In another stunning case in 2009, a 92-year-old woman in Chile was found to be carrying a 50-year-old lithopedion discovered incidentally during an X-ray for a fall. She had lived her entire adult life unaware of the fetal remains inside her.

What Does a Stone Baby Look Like?

While the term “stone baby” conjures mythical images, the actual appearance is deeply human — and deeply poignant. The calcified fetus often resembles a white or grayish stone, but with features such as limbs, a head, and even facial structures still identifiable under the mineral layers. In some cases, skeletal remains are encased in a hard shell, and the internal organs may have partially decomposed or mummified.

Is Lithopedion Dangerous?

Surprisingly, most cases are not life-threatening. Because the fetus is fully calcified, the risk of infection is low. However, the condition can cause complications like abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, or pressure on nearby organs. In some cases, the stone baby is discovered only during surgery, imaging scans, or post-mortem examination.

If diagnosed, removal is generally recommended — especially if the lithopedion causes discomfort or health issues. But some women live with them for years without ever knowing.

Lithopedion – Mystery of the Stone Baby

The Emotional and Psychological Angle

Beyond the biological strangeness lies the emotional weight of the condition. For many women who learn they’ve been carrying a lithopedion, the discovery is traumatic. It brings to light an unrecognized or unresolved pregnancy — often accompanied by grief, confusion, or disbelief.

In some cultures, lithopedion is wrapped in myth and superstition. In rural communities, it’s not uncommon for women to interpret the condition as a divine punishment or spiritual burden. This makes medical education and culturally sensitive communication essential when managing such cases.

Modern Medicine and Prevention

Thanks to advancements in ultrasound imaging and early prenatal care, lithopedion is now incredibly rare. Ectopic pregnancies are usually detected and treated within the first trimester, long before calcification could occur. Treatments may include medication or surgical intervention, both of which are highly effective.

Yet, the existence of lithopedion serves as a reminder of what can happen in the absence of modern care. It underscores the importance of maternal health services, especially in resource-limited areas.

A Curious Medical Legacy

Lithopedion occupies a unique place in medical literature — a reminder of the body’s strange wisdom and its ability to protect itself under extraordinary circumstances. It’s a phenomenon that fascinates doctors, mystifies patients, and even inspires artists and storytellers.

The “stone baby” is not just a medical rarity; it’s a testament to the enduring mystery of the human body — one that still leaves doctors humbled and awed.

Did You Know?

- The oldest known lithopedion was carried for over 60 years.

- The term was first coined in 1720 by German physician Friedrich Kuchenmeister.

- Most lithopedion cases are found in women over 40, usually long after menopause.

Final Thought

In a world that often celebrates medical marvels and technological wonders, the story of lithopedion is a gentle but eerie reminder: nature still holds secrets far stranger than fiction. And sometimes, those secrets are hidden within us — waiting to be discovered.

References

- Ciftdemir, M., & Kiratli, P. (2008). “Lithopedion: Report of a Case”. Emergency Radiology, 15(3), 221–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-007-0676-6

- Saglam, M., Cengiz, H., & Bayrak, Ö. (2012). “A 40-Year Literature Review: What We Know About Lithopedion?” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 285(4), 1129–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2159-5

- Pradhan, S., & Singh, K. (2015). “Lithopedion: A Rare Cause of Abdominal Mass”. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 9(3), QD01–QD02. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/11509.5752

- Fernandes, N., & Chibber, P. S. (2010). “Incidental Finding of a 45-Year-Old Lithopedion”. Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging, 20(4), 334–336. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-3026.74355

- Paré, A. (1582). “Anatomical Account of a Calcified Fetus”, in Works of Ambroise Paré. Paris: Gabriel Buon.

- Kitchenmeister, F. (1867). “On the Formation of Lithopedion”. British Medical Journal, 1(347), 622–623.

- Kaunitz, A. M., & Grimes, D. A. (1995). “Ectopic Pregnancy: A Review”. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 85(2), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(94)00341-0

- Fitzpatrick, K., & Knight, M. (2014). “Ectopic Pregnancy and Its Complications”. In Berek & Novak’s Gynecology (15th ed., pp. 469–489). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- World Health Organization. (2018). “WHO Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Ectopic Pregnancy”. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications

- Killen, J. (2009). “Lithopedion: Case Report and Review”. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 38(2), 228–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.00967.x